Farming through the Ages

Sunday, 20th June 2010

Gear Farm, the home of the Hosking family since 1933, is the site of a large hillfort, dating back to perhaps 3000 BC, which was the subject of excavations and a TV programme by the BBC’s Time Team in 2001. For this event we had the benefit of two experts, James Gossip from the Cornwall Archaeological Unit (Cornwall Council) and Mary Combe from the Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group, each assisted by a member of the Hosking family. The group of 43 was divided into two parties, one going with James and the other with Mary and then, after a swap, our experts kindly repeated their tours for the other party.

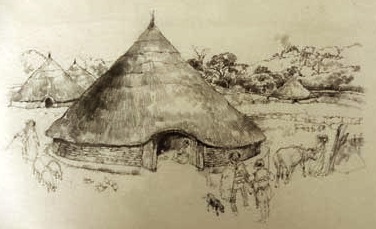

Gear Farm historical drawing

Gear Farm historical drawing

James Gossip started his tour by taking us to a barn containing display cases which housed a host of artefacts discovered by Rex Hosking and his family over the years. Also on display were drawings and photographs prepared by the Time Team, who investigated the site using excavations and geophysical surveys. A few flint items might possibly have belonged to the nomadic hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period, 10,000 – 4,000 BC. The flint would likely have come from beach pebbles, the nearest rock source being Beer in Devon. Flint working was better developed in the subsequent Neolithic period (4000 – 2500 BC) and collected pieces included what might have been a scraping tool and a chisel-shaped arrow head.

Gear’s history probably started about 3000 BC (14C dating), but its main period was 150 BC – 300 AD, late Iron Age to Romano British. Artefacts from this time included a Cornish-style carved stone bowl, made from rock obtained from Gedonning(?) Hill; and pottery made from gabbroic clay. The clay is found in a small area of c.7 km2 near St Keverne but its use was widespread. About 90% of ceramics in Cornwall were made from it because it had the property of not disrupting when fired. Among other stone objects discovered were a saddle quern, a pounding stone and a rotary quern, the latter shaped like a thick discus with a central hole, probably made by an iron tool, for feeding corn to the grinding surface. It was thought to date from about 150 BC.

Some 2000 to 3000 Iron Age sites are known in Cornwall, over 30 of them in the Helford catchment. Mostly these were ‘rounds’, settlements surrounded by a bank and ditch, probably occupied throughout the year by people whose main activity was farming. A few sites were more substantial: hillforts and their coastal equivalents, cliff castles. Defended by deep ditches and earth or stone ramparts, these forts are thought to have been social and trading centres for the surrounding settlements. Gear was a large hillfort, enclosing an area of 15 acres (6 hectares). Only two others of comparable size are known in Cornwall. Interpretation of the geophysical data suggests the presence of about 16 round dwellings within the fort.

Leaving the barn, we walked around the fort along its defensive ditch. The adjoining rampart was impressive, a very steep bank of earth and stones about 16 feet (5m) high in places, now covered by woodland. In its time, however, it would have been relatively much higher, because the ditch had been partially filled in during the 19th Century as an attempt at landscaping by the Vyvyans of Trelowarren, anticipating a visit by Queen Victoria in 1846. The true bottom of the ditch, determined by the Time Team, was about 9 feet (3m) below us. About three-quarters of the way around there was a gap in the rampart, thought to have been the sole entrance to the hill fort. There is some evidence of an approach way and a zig-zag track to nearby Mawgan Creek.

We walked up-slope to the centre of the hillfort, now a large field of grass and clover. Queen Victoria, had she visited Trelowarren, would have been presented with a vista of ancient settlements at Gear, Caer Vallack and Bonallack, now not possible because of subsequent tree planting. Caer Vallack, a well-preserved round close to Gear, may have been a chieftain’s settlement. James expanded on life in the hillfort and settlements. The basic way of life probably changed little from the Iron Age through the Roman period. Romans had already been trading for tin prior to occupation and were apparently content to maintain that arrangement, without taking control of the mines. There are signs of increased trading, for example fragments of amphorae. For the Iron Age –Romano British people, salt was available from Coverack and Kynance, fishing was practised, suggested by holed stones possibly used to weight lines and by woven fish nets. Piles of cockle shells are known from Tremayne. Oak was used for construction and hearths, hazel for charcoal and coppiced roundwood for high temperature firing of furnaces. Spelt wheat, barley and oats were the principal crops, augmented by nuts and berries. Because of the acid soil, Cornwall has a poor record of animal bone remains, but there is evidence for cattle, pig/boar and Soay-type sheep. It is likely that the soil was ameliorated by manure and the spreading of seaweed.

The occupancy of Gear hillfort seems to have ended around 300 AD, for reasons unknown. The first written reference to it was in 1262. It had brief fame in 1643 as the Gear Rout, when 300 Royalist troops and 40 horse were pushed back by advancing Parliamentarians.

Very many thanks to James Gossip for his lively and thoroughly absorbing tour which brought an ancient hillfort back to life.

Mary Combe explained that the Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group is an independent organisation which exists to advise farmers on a wide range of topics, with the aim of improving productivity and profitability and reducing working costs, while at the same time benefitting the environment and conserving biodiversity. It provides practical information on diverse matters such as soils, water, nutrients, hedgerows, greenhouse gases and renewable energy, but couples these with advice on landscape, historical importance and wildlife habitats. Gear Farm is a superb example of the coordination of farming and environmental stewardship. In its early days it was part of the Trelowarren estate, the farmer, as tenant, renting the cows and profiting from the milk. It was bought from the estate in 1948, as a large farm of over 250 acres worked by 8 men. Subsequently it was divided among three brothers and is currently an 80 acre organic farm, famous, among other things, for producing the best pasties in the region, with all the ingredients coming from the farm. Walking from the car park towards Tremayne creek we stopped at a field containing rows of potatoes, swedes and onions. The farmer told us that the potatoes were early varieties, to crop before blight took hold. One, a Hungarian variety, was said to be blight resistant, though not drought resistant. Parts of the onion planting were thick with weeds, but these were soon to be cleared by machine hoe between the rows and then hand weeding. The farm doesn’t use herbicides. In the mean time the weeds provided a welcome habitat for ladybirds and other beetles.

Farther down the track, Mary sold us that a feature of the Cornish landscape was its age, many of the hedges being medieval, or at least 150-200 years old. Perusal of old maps was helpful in determining the age of a hedge, while an empirical method involved counting the number of woody species, such as blackthorn and sycamore, in a 30 metre stretch and reckoning 100 years for each species. Ancient hedges were often built curved, to give shelter from different wind directions. Crops such as corn, potatoes and hay, requiring transport, were planted near the farm house separated by ordinary hedges. Cattle, being mobile, could be grazed farther away and so hedges bordering lanes to pasture and water supply were often stone-faced to prevent cattle damaging them. Farm hedges were also a key timber source. For example, sycamore or ash logs would be laid on the ground and covered by a layer of bramble to make a base for hay and straw ricks. Because of their value, hedges used to be cut bare, whenever a farm changed hands, so that they could be properly assessed. However, this practice has been modified, following FWAG advice, because hedges are extremely important for wildlife, providing shelter, food, nesting places and corridors between habitats. Ideally they should be at least 1m tall and 1.5m thick, continuous, with a 1m herbaceous verge to protect the roots and the tops not trimmed until Nov-Feb, after berries have fruited.

Passing on, we came to the site of a former hedge. The soil here was poor, with few nutrients, but weeds and wild flowers were numerous, plus some small oak saplings perhaps indicating acorn dispersal by jays or squirrels. It is likely that brambles will follow, a plant extolled by Mary as good for birds and insects. Native species such as these, unlike imported plants, are in tune with the environment and capable of dealing with acid soils and a salty atmosphere. Alien species belong in gardens, not in the countryside. The next stop brought a view across the Helford to Merthen Woods, formerly coppiced to provide charcoal for the mines and containing a pack-horse track up which lime and seaweed were taken from the quay to farms, to counteract acid soils. In the foreground, grassy fields swept down to the National Trust woodlands flanking Tremayne Creek on our right. One section, too steep for vehicles, had been allowed to revert to woodland and showed a healthy development of sweet chestnut, birch, sycamore and ash.

Grasslands are valuable to the farm for hay and silage (cut in May), but are also important for wildlife, such as voles, spiders, butterflies and skylarks. The last need undisturbed conditions when nesting and may also find these in spring cornfields ( although these can be too dark) and in daffodil fields not yet cleared after flowering. One field in particular attracted attention. It was a favourite hunting ground for barn owls, possibly the ones which had nested in Tremayne boathouse last year, and its long grass would be deliberately left uncut until August, apart from a winding swathe of shorn grass over which voles might run (at their peril).

Discussion turned to the absence of honey bees and Mary said that there was a problem for insects generally. Availability of nectar at different times of the year was a key consideration. Blackthorn, gorse and hawthorn had largely finished flowering. Some clovers and creeping thistle were current sources. Umbellifers provided little. August was often a poor month, but nectar was available from ivy. Returning towards the car park, Mary opened the door of the camp-site shower cubicle to reveal an owl box, used for roosting by young barn owls (the shower as a consequence being out-of-bounds). In conjunction with another box in the barn and perching posts at either of the field, it epitomised Gear Farm’s sensitive consideration of wildlife in all its forms while at the same time running a very successful farm.

The HMCG would like to thank Mary Combe and Mr Hosking very much for an extremely informative and enjoyable afternoon.